Living Democracy

I spent a good portion of my academic career writing about apathy.

As a student of political communication in the 80s and 90s, when most people got their news through television, I was drawn to questions about how the media influenced political engagement.

The answers weren’t pretty.

Cable television had fragmented a once-centralized information environment, giving people more choices for news and entertainment than they could ever need. This left news producers in a perpetual race to attract and hold the attention of people who could choose MTV or Entertainment Tonight over Meet the Press. The result was news content that often emphasized the sensational over the substantive—news of dubious value to people trying to make informed political choices.

But the biggest problem was television itself.

We had built our political system around television. It was how candidates and officials reached voters and how anyone hungry for attention could be heard. If a tree fell in the forest and it wasn’t covered by CNN, did it make a sound?

The problem was that television was miscast as a political medium.

Television is designed to entertain us. To lull us into a state of complacency. To help us disengage.

Armed with a snack and a remote, we can slump back in our chairs and let television wash over us.

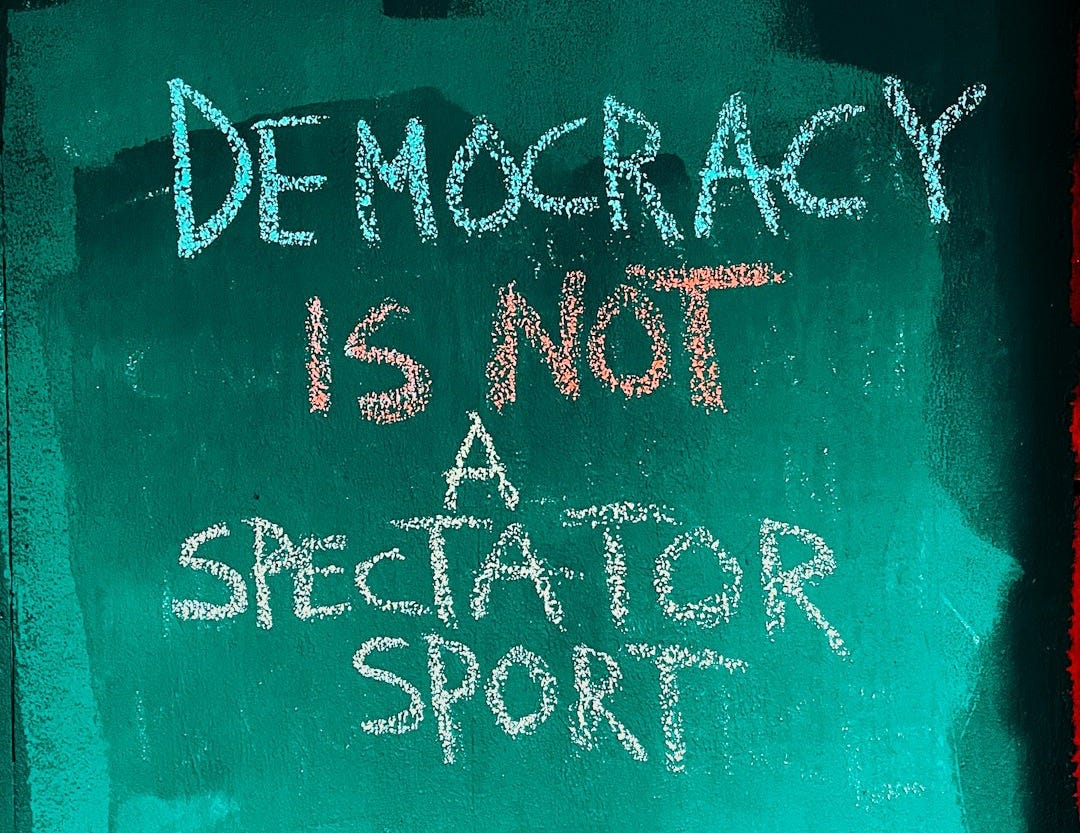

It turns us into spectators.

My concern during this time was that television was assisting and perhaps fueling our diminished political engagement. At a time when turnout in presidential elections declined and people felt estranged from the government, it was difficult to make a convincing case that a healthy democracy required active participation.

Plenty of people didn’t care. The economy was roaring. The Cold War was ending. Things were widely perceived to be good. Why waste your time on politics when you’re having so much fun?

I saw this attitude reflected in how my students at the time reacted when we talked about their disinterest in politics. My exhortations about the value of participation were met with more than a few eye rolls. It’s what led me to write an American Government textbook around the theme of political involvement.

As Chris put it in his post last Tuesday, democracy has to be lived. It has to be practiced every day.

And—unlike in the late 20th century—he notes that today people are quite engaged:

When it comes to actually living and practicing our democracy, I honestly think we are living in a golden age. Chaotic, scary, dangerous, and with an uncertain future—I will grant you all of that. However, American democracy is still, in this moment, very much alive.

Chris points to record-setting anti-Trump protests, widespread self-publishing on social media (including sites like Substack), and the pounding Republicans are taking at the ballot box as evidence that democratic engagement is alive and well. People in large numbers are using their rights to free assembly, free expression, and voting in free elections to push back against the illegitimate actions of the Trump regime.

When viewed through this lens, our collective engagement is the tool that is saving us from the harms that grew out of years of collective disinterest.

Because when we foreswear civic participation we silence our own voices.

Those who looked away with disinterest permitted individuals who wanted to engineer the political system to their selfish advantage to operate without the resistance they would have encountered if people were involved like they are today.

And if the political actions of these engaged elites produced obscene inequalities that allowed them to live privileged and apart from a great many who saw their livelihoods shattered, their earning power diminished, and their futures dimmed—well, that’s just collateral damage for a later time.

For our time.

For a time when people started tasting the bitter fruit of that period of widespread complacency.

For a time when they were finally roused to action.

It took a reactionary movement using force to impose what they could never earn through elections to kindle the kind of mass engagement that can no longer be ignored by politicians.

A mass engagement that allows the shouted wishes of ordinary individuals to threaten the elites that Georgia Sen. Jon Ossoff cleverly labeled the Epstein Class—the privileged few who counted on a disengaged public to let them write the rules to rule the world.

Yes—this moment is filled with uncertainty. But the threat to our democracy began years ago, when so many people weren’t looking.

This leaves the promise to repair our democracy to our present reengagement.

To our seeing democracy as a living organism that needs to be nurtured with our vigilance.

To our using the Internet and social media—tools that didn’t exist thirty years ago—to organize and amplify our interests and demands.

The social media environment is very far from perfect. It shepherds us into information silos and blasts us with untruths, and in so doing poses threats to effective self-governance that are different from but no less dangerous than the ones posed years ago by television. But social media can also allow us to speak our minds and channel individual wishes into collective democratic action. In this regard, it is the anti-television: a medium that energizes instead of enervates.

It allows an engaged people to take action—to take the actions necessary to preserve a democracy that we allowed to be hijacked through our inaction.

As Chris wrote:

Our democracy exists to be used, practiced and lived. And honestly, I’m not sure if it has ever been used, practiced and lived quite as much as it is right now.

This outcome was not assured. There was no guarantee that we would respond collectively at a moment when our collective actions would be the last defense against tyranny.

But we have.

We are living democracy so that democracy may live.

Next step is to allow all Americans (Wash. DC, Puerto Rico, other American Island territories) to vote for president who wins by popular vote.

thanks for the succinnt recap of television (as spectator sport) and the slide of cable channel news towards feeding the sensational vs. the sane . . . . Very clear and helpful info.